Welcome to the third copy of my newsletter about nerve root pain. As I continue with my research, I have been saving all the best pictures of spinal anatomy I come across. So I thought I’d put them together in one place as a visual tour of our lumbar nerve roots!

📸 *Please note there are pictures of cadaver dissections in this email.* 📸

Starting at the top. The spinal cord ends at the level of L1/L2. Here you can see it terminate at the conus medullaris, in the middle of the picture. The cauda equina continues on down the spinal canal.

(ref)

The cauda equina is protected by the dural sac (also called the thecal sac) as you can see here (artificially coloured in the top image)

Here is what the cauda equina looks like with the dural sac partially taken away.

And here it is with the dural sac opened completely.

And of course this is all going on inside the spinal canal, seen here in cross section.

(ref)

By the time it gets to the lumbar spine, your spinal canal is about the diameter of your index finger

(ref)

The nerve roots first bud off from the spinal cord as nerve rootlets. Then they blend into the nerve roots that make up the hanging tail of the cauda equina.

(ref)

Some roots will be anterior (ventral) roots, shown here in red. Some will be posterior (dorsal), shown in blue.

(ref)

Looking closer, here are some nerve roots in cross section.

And closer still…

(ref)

Zooming out again, here are the nerve roots exiting the dural sac. You can see the dorsal and ventral roots.

(ref)

Once they exit the dural sac, the dorsal and ventral roots are bundled together in the dural sleeve. (Pic from the highly recommended chirogeek.com)

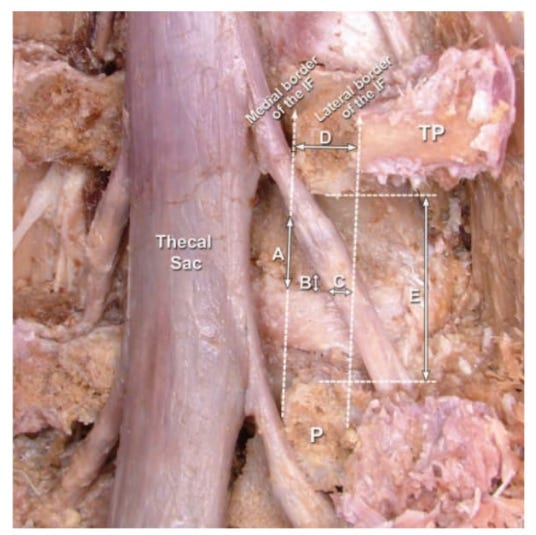

Outside the protection of the thecal sac, the roots are more vulnerable to compression. Partly this is because they are held a bit more "fixed", with less wiggle room, as you can see here.

(ref)

The position of the roots relative to the disc is important. As you can see here, the nerves are actually kind of out the way of the disc when they exit through the foramen (and even so, far lateral disc bulges are relatively rare). Where they are most vulnerable to a disc herniation is just as/after they exit the dural sac. So if you imagine a paracentral L4/L5 disc bulge in this picture, the transiting L5 nerve would be affected.

(ref)

Seen also here.

(ref)

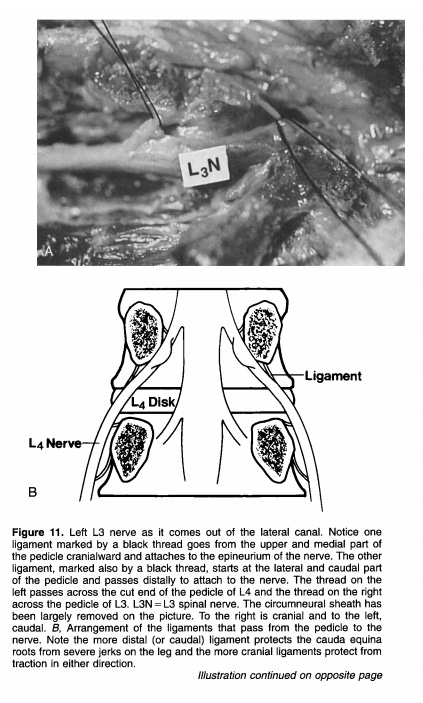

We can see how ligaments contribute to this positioning.

(ref)

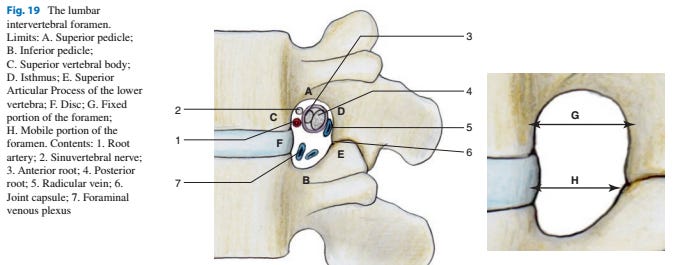

Let’s continue to follow the roots. Next, they pass through the intervertebral foramen on their way out of the spinal canal.

(ref)

The lumbar spinal nerve never takes up more than 1/3 of the space of the foramen. But it does share its space with vessels and ligaments, and the sinuvertebral nerves which are heading back *in* to the canal.

(ref)

The ganglion is almost always found under here, under the pedicle, in the foramen. Sometimes it is a bit medial or lateral.

(ref)

Then, after the ganglion, the roots become the spinal nerve (blue) which quickly branches into the dorsal (yellow) and ventral (red) rami which go off and do their own thing.

And if we go any further we will have left the nerve roots behind, which ends our tour!

That’s it for this edition. Please feel free to get in touch with me and to share the email with friends and colleagues. If you see any errors, too, please let me know.

Until next time,

Tom

Many thanks Tom for sharing your knowledge