Thanks for reading the 61st edition of my newsletter. This newsletter tracks my work on lumbar nerve root syndromes aka sciatica.

Beyond the tweets, memes and infographics, what do we actually know about the relationship between disc herniations and radicular pain? I went through all the evidence and drew some conclusions. Please do let me know if I’ve missed anything important!

Herniations and radicular pain

Asymptomatic disc herniations are common (except for extrusions).

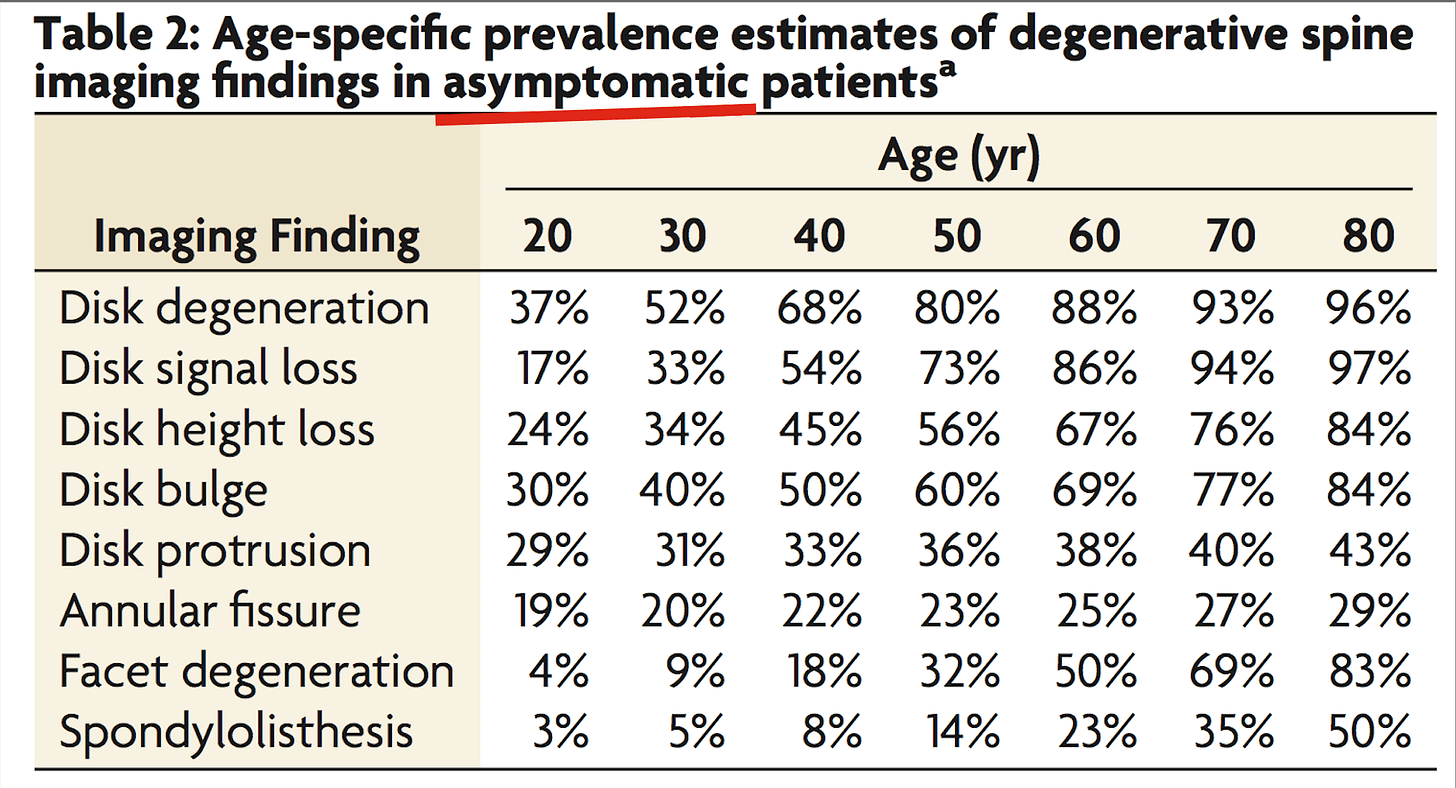

It’s well-known that herniations are common in asymptomatic people. We all know the table…

The wrinkle is that this table only mentions disc protrusions. But asymptomatic disc extrusions are not that common1. According to a less-cited Brinjikji paper, only about 1.8% of asymptomatic people have a disc extrusion.

This fits with findings from a study by Suri and colleagues, who followed asymptomatic people and intermittently gave them an MRI to see what was going on. Only five of the 123 people got a disc extrusion, and all five of them also got radicular pain2.

It seems that asymptomatic extrusions aren't a big thing.

But I don’t want to overstate my case - asymptomatic herniations in general are still pretty common. As Brinjikji and colleagues report, 29% of asymptomatic people in their 20s have a disc protrusion, and this rate increases gradually through life, up to 43% of asymptomatic people in their 80s.

How can you have an asymptomatic herniation? Lots of reasons3, but here's some:

Some herniations are not near transiting nerve roots (for example upper lumbar protrusions, or central or far lateral protrusions).

Some herniations are presumably not that chemically-active, so that even if they are close to a root they don’t irritate it.

Some herniations develop very slowly, so that even if they do encroach on a nerve root the root has time to adapt.

All the non-local, broader systemic factors that might make someone more or less predisposed to pain, such as their immunological profile.

In any case, the conclusion of this section: disc herniations do not always come with pain.

Herniations are more common in people with radicular pain.

For example,

In the review I mentioned above, Brinjikji and colleagues found that 1.8% of asymptomatic people had a disc extrusion, compared to 7.1% of symptomatic people. And 19% of people had a disc protrusion, compared to 42% of symptomatic people 4.

Boos et al. found that 22% of asymptomatic people had herniation-induced nerve root compression (which was mostly minor), compared to 83% of people with radicular pain (which was mostly severe).

Konstantinou et al. found that 32% of people with somatic referred pain had nerve root compression, mostly caused by disc herniation (some stenosis), compared to 60% of people with radicular pain.

van Rijn et al. didn't compare symptomatic to asymptomatic people, but the symptomatic to the asymptomatic side of the spine in people with radicular pain. The asymptomatic side had a herniation 33% of the time, whereas the symptomatic side had a herniation 74% of the time.

In other words, people who have sciatica are, as you’d expect, more likely to have a disc herniation than people who don’t have sciatica.

The importance of disc herniations diminshes over time

For example,

El Barzouhi et al. looked at the the MRI images of a group of patients one year after their treatment. They found that about a third of people who got better still had a disc herniation, and... about a third of people who didn't get better also still had a disc herniation. Another way of looking at the data: of all the people who still had a disc herniation a year after treatment, 85% felt better5.

In a similar study, Barth et al. found that two years after surgery, many patients still had herniations (remnants and reherniations), but these findings didn't correlate with their clinical status.

Fraser et al. found much the same thing, 10 years after treatment - "the presence or absence of herniation had no significant bearing on a successful outcome"

Essentially, after a year or so, most people's pain seems to be doing its own thing, irrespective of what the disc is doing! It seems that herniations are generally short- to medium-term trigger of radicular pain. Presumably they ‘spark’ the neural mechanisms of pain such as neuroinflammation, structural nerve damage, ectopic sites, and local scarring and tethering; and, once sparked, those mechanisms are partially self-sustaining.

Bonus ?fact: People with leg pain but no back pain might be more likely to have an extrusion than a protrusion

Just an aside based on two small studies:

Pople and Griffith found that 96% (!) of people with sciatica but no back pain had a disc extrusion.

Reihani-Kermani found that people with sciatica but no back pain were 6.5x more likely to have an extrusion. And, if their radicular pain increased as their back pain decreased, they were fully 10x more likely.

Now, let’s look at…

Herniation size and radicular pain

Herniation size is (probably) not associated with the degree of pain

For example,

Dunsmuir, amongst 56 patients - "There is no direct correlation between the size or position of the disc prolapse and a patient’s symptoms".

Karpinnen, amongst 160 patients - "Magnetic resonance imaging is unable to distinguish sciatic patients in terms of the severity of their symptoms"6.

Mariajoseph, amongst 122 patients receiving a microdiscectomy - "Disc fragment weight had no effect on the severity of pain".

Seo, amongst 43 patients undergoing conservative treatment - "No statistically significant correlation was evident between symptom severity and disc volume".

Not quite the same thing, but related - Jensen et al. found that amongst patients with radiculopathy, nerve root touch caused as much leg pain as nerve root displacement or compression.

This appears to conflict somewhat with the fact that, as we’ve seen, extrusions (bigger) seem more likely to cause pain than protrusions (smaller). I think the thing is that once a herniation is painful, it doesn't much matter if it’s big or small.

(Of course, this is all just pain. Herniation size does seem to be associated with the degree of neurological deficit).

Herniation size is (probably) not associated with the eventual clinical outcome

For example,

Gupta - "There is no statistical association between the size of a lumbar disc herniation and the likelihood that a patient will fail conservative treatment and ultimately require surgery".

Masui - "Clinical outcome did not depend on the size of herniation" after seven years

Modic, amongst 246 patients with acute radicular pain or back pain - "there was no relationship between herniation type, size, and behavior over time with outcome."

So, the size of the herniation doesn't seem to matter much.

That might be because of measurement problems when it comes to MRI (which, after all, is not the eye of God; and what would upright MRIs have found?).

But even accounting for measurement problems, it seems that size doesn’t matter much. Why not? Well, nerve roots are relatively fixed in place on the disc-side of the spinal canal, which means that a herniation doesn’t have to be particularly big to add significant mechanical pressure to a root anyway. And radicular pain is in large part driven by discogenic chemical irritation, which renders the actual size of the herniation less important.

So a disc herniation is not like a vice that causes pain through mechanical pressure, and causes more pain the more tightly it is wound. Considering the role of this chemical irritation, a closer analogy is that a herniation is like putting chilli powder on your fingertip and poking, or even just touching, your eye. The contact is important, and more pressure is surely not desirable, but the pain is mostly caused by chemical irritation.

Change in herniation size is associated with a change in pain

As we know, herniations change in size over time, most of them shrinking as they are resorbed by the immune system, but some growing in size as more disc material escapes. And these changes in size do seem to go along with changes in pain. For example,

Seo et al. split patients into a group whose herniations got smaller over time and a group whose herniations got bigger. Both groups' leg pain improved on average, but pain improved more quickly in the group whose herniations got smaller7.

Ahn et al. found that a decrease in disc size of more than 20% correlated strongly with a positive outcome. 18 of 19 people whose discs decreased by 20% had relief of most or all of their pain.

Fagerlund et al. found a "significant positive correlation between the improvement from sciatic pain and the reduction in the size of the individual hernia", amongst 30 patients

Kesikburun et al. found that patients whose discs completely resorbed also had less pain, whereas patients with partial or no resorbtion did not, amongst 40 patients

Komori et al. found that change in herniation size "mainly corresponded to clinical outcomes but tended to lag behind improvement of leg pain", amongst 77 patients. The lag suggests that the two might not actually be closely related; discs resorb and people get better but the resorbtion might not be the cause of the improvement.

There are exceptions, but it seems to be a trend that a change in disc size is associated with a change in pain.

It seems kind of contradictory that the size of a herniation isn't associated with pain, but change in size over time is. Maybe it's not the shrinking per se that causes a pain reduction, but the fact that a shrinking disc is also resolving as a biochemical event - fizzling out, becoming less inflamed... To put it another way, 'change in herniation size' might be a proxy for 'inflammatory process doing its thing, body working its way back to normal'.

Of course, by now we are looking at a lot of quite small studies, with inherent measurement errors, so I’ve got to be careful that I’m not just reading tea leaves. All conclusions about herniation size are tentative.

General conclusions

Although asymptomatic herniations are common, asymptomatic extrusions are not that common. And, as expected, people with radicular pain have more herniations than people who don’t have radicular pain. That said, the importance of symptomatic herniations decreases over time, because herniations are generally a short- to medium-term trigger for radicular pain. [EDIT: ‘Spark’ or ‘catalyst’ are good analogies; ‘kindling’ is probably even better].

Once a herniation is painful, it’s not necessarily the case that a bigger herniation is more painful, or vice versa. A bigger herniations also doesn’t mean a worse outcome in the long run. That said, as herniations get smaller people do seem to feel less pain.

That’s it!

It strikes me that the middle ground is a good place to be on this one…

As I say, please let me know if you think I’ve missed anything important.

Til next time,

Tom

P.S. Work on the republication of Sciatica Book 1 (now retitled ‘Understanding Sciatica’) continues! Nearly there… Here’s some of the pictures and here’s the work in progress cover.

Extrusions are larger, uncontained herniations. See here for a thread.

A weakness of this conclusion is that the study’s definition of radicular pain was very loose

Crucially, what the existence of asymptomatic disc protrusions doesn’t mean is that herniations are unrelated radicular pain. That is an over-interpretation. It would be like saying ‘campfires don’t cause forest fires, because lots of people have campfires that don’t cause forest fires’, or ‘speeding doesn’t cause car accidents, because lots of people speed and don’t get in accidents’. (If anything these analogies under-sell my point because campfires and speeding cause forest fires and accidents far less often than herniations cause pain).

I recently ran a twitter poll that found that 17% of people believe that disc herniations are unrelated - like, fully unrelated - to radicular pain. I assume the people answering this way have been misled by the flood of info on asymptomatic herniations. But lots of things can be asymptomatic sometimes! The flu, for example.

Note these people had spinal pain in general - unfortunately no such big review exists for radicular pain specifically.

This was a mixture of surgical and nonsurgical patients. Some surgical patients still had a disc herniation - presumably either remnants left in despite the op or, more likely, reherniations (which are commonly ‘silent’) .

Interestingly, larger disc herniations were associated with a higher likelihood of having radicular pain, as opposed to sciatica.

The authors also noted that amongst people whose pain got worse, herniations may have shrunk or grown, with no pattern.

Brilliant work as ever Tom, thanks very much for taking the time to write this.

Excellent, thank you! Super useful review for me as I tackle some revisions to my own content on this topic. Barzhou et al. was blowing my mind a little, very interesting result… and then I discovered it was already in my bibliography, and had blown my mind before. 😜

One question: what means "Some herniations are presumably not that chemically-active"? Elaborate a little on that?