Does bending and lifting cause disc herniations?

Cautious Kennys vs Cavalier Karens

Thanks for subscribing to my newsletter, which tracks my work on lumbar nerve root syndromes aka sciatica. If you no longer want to receive these emails, I no longer want to send them to you. Please scroll to the bottom and click ‘Unsubscribe’.

[UPDATE: a new review on this topic supports the conclusions in this post].

Does lifting and bending1 cause disc herniations?

Two groups argue over the science.

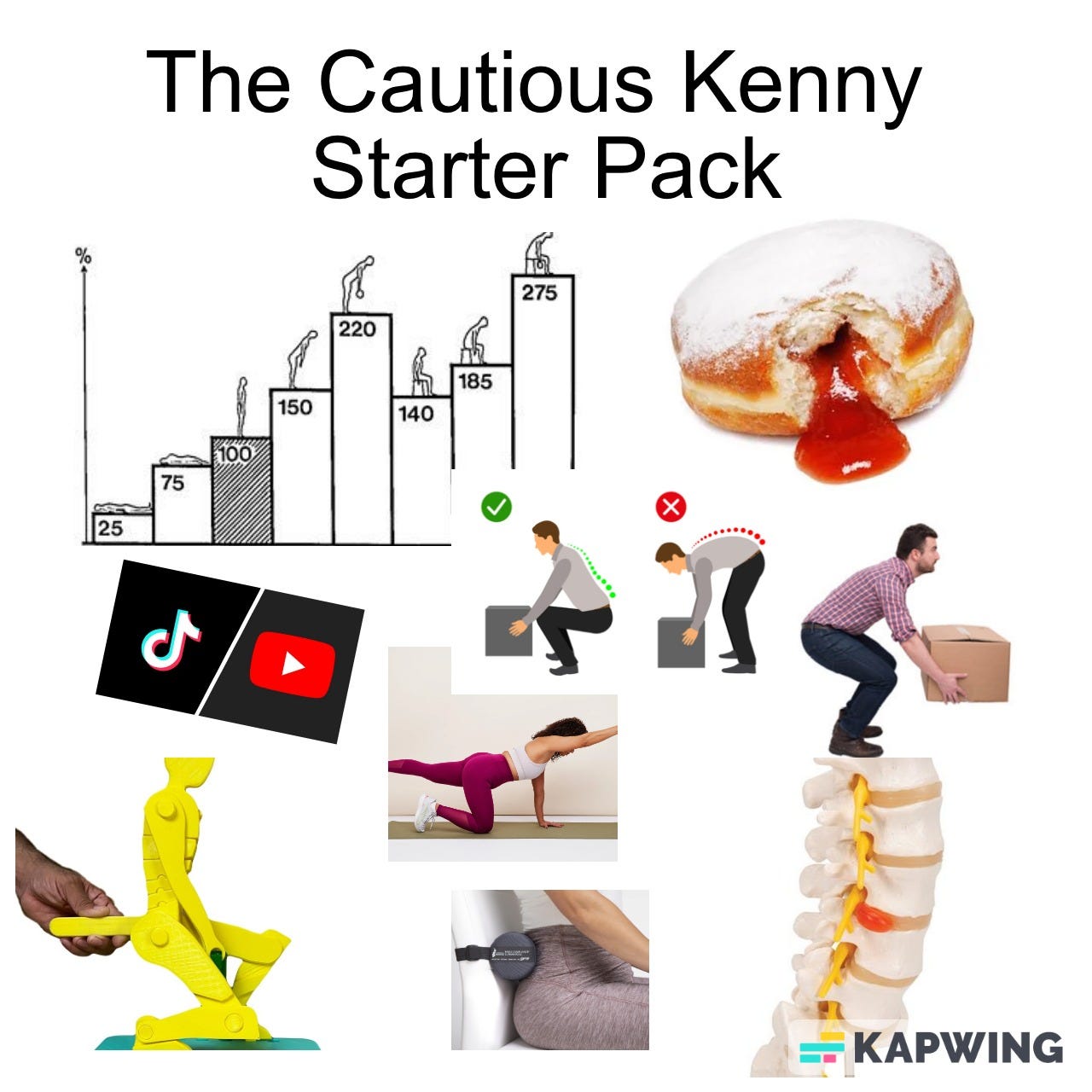

One group say that lifting and bending do cause herniations, so we should avoid them (to a lesser or greater extent). Keep your spine in ‘neutral’, and don’t overdo it. Let’s call this group the Cautious Kennys.

The other group say that lifting and bending do not cause herniations, so we shouldn’t avoid them at all. Lift, bend, heave and stoop away! Let’s call this group the Cavalier Karens2.

Let’s watch them argue it out.

Battle 1: Dead discs vs computer discs

The Cautious Kennys didn’t make up their message of caution out of nowhere just to scare everyone. Decades of research shows that bending and lifting are one route, probably the main route, to a disc herniation3. If you take dead pigs’ discs, or dead sheeps’ discs, and put them in a disc-flexing machine, and then flex them over and over again - simulating cycle after cycle of bending and lifting - they do indeed herniate in just the same pattern that we see humans’ discs herniate.

Why does that happen? Well, the inside of a disc, the nucleus, is a kind of watery, semi-fluid substance. It has the consistency of phlegm, or porridge, or toothpaste, or watery crab’s meat, depending on who you ask. When you’re standing up straight, the watery nucleus accepts all the force of bodyweight, muscle contraction, and anything you’re carrying, and pushes that force outwards in all directions.

But when you bend forward, the watery nucleus pushes almost all of that force in one direction: backwards. And when you bend forward and lift something heavy, that adds even more force to the equation. So bending and lifting is double trouble. If you do it enough, say the Cautious Kennys, then all that backward-directed force will start to tell… the watery nucleus will prod and push through the more solid outer part of the disc, eventually escaping through the outermost layer - splurge! - and into your spinal canal. Which is a disc herniation.

Cautious Kennys take this to mean that bending and lifting are the main route to disc herniation, and that we should therefore avoid them.

How could Cavalier Karens argue with that? Well, they point out that there’s only so much you can reason from dead discs in lab conditions. When you use computer simulations to add in the push and pull of the muscles, ligaments etc. that surround the disc, the Cautious Kennys’ picture is not so simple. Sure, if you avoid bending to lift then you might, theoretically, reduce the amount of force your nucleus pushes backwards… but in doing so you only increase the amount of force going through the spine in other ways.

For example, let’s say you have 50 boxes to move into a U-haul. You don’t want to bend your low back, so you lift with a nicely extended low back. According to Cautious Kennys’ theory, this reduces the amount of backwards-pressure that pushes through you discs. But, in order to keep your low back in that nice extended position, you have to contract your spinal muscles a lot more. In doing so, you scrunch more force through the disc, i.e. the force of that extra muscle contraction. And that’s not all: with all the extra effort it takes to keep your low back in a nice extended position your muscles will fatigue earlier, leaving you vulnerable to an overuse injury!

In other words, there’s no get-out-of-injury-free card! Reducing risk in one way only adds it in another.

In fact, some radical Cavalier Karens argue that you should deliberately lift with a rounded low back, because that allows the ligaments of the spine to take up some of the load of those boxes, just as they were designed to do! This makes lifting with a rounded low back more energy efficient. Cautious Kennys are ready for this one though: they would reply that deliberately lifting with a bent low back is a bad idea because, once you’re got about 25 boxes in that U-haul, your ligaments will start to stretch and slacken. Now they’re not doing their job as well, and you’re inviting an injury that way!4

So this battle has turned into a bit of a melee. There’s no get-out-of-injury-free card; lifting technique - whether it’s a bent or extended spine, or a squat or stoop approach - is trade-offs all the way down.

Now, do I believe that that all lifting postures are the same, that it’s all just relative? Not really, I’m sure if we had a computer with the Eye of God that could model this all a billion times then it would tell us that some positions are worse than others, and this might very well be bent-spine lifting5. But what seems clear, once the Cavalier Karens have presented their evidence, is that there’s no categorically safe position and no categorically dangerous position, because making yourself (theoretically) safer in one way only increases (theroetical) danger in another way.

And that’s not even accounting for the fact that, no matter what lifting style you adopt, bending your low back is inevitable! Yes, perhaps suprisingly, even when you do a perfect ‘manual handling approved’ lift the low back is probably flexing. [H/T Greg Lehman]. So to a certain extent the debate about whether to try to avoid low back flexion is moot when some flexion is inevitable anyway.

So what should you do? Well, from a biomechanical point of view, a sort of ‘freestyle’ attitude to lifting and bending is probably best. That means being comfortable, both physically and mentally, in a very bent or very extended position, but that spends most of the time in the large range between the two6. A kind of ‘master of all positions’. You can think of this as having a range of different movement strategies to get the job done and to switch between to distribute the load.

So who wins Battle 1; is flexing and bending really worse for the disc? Well, I do think that Cautious Kennys are correct: all else being equal, bending while lifting is probably is ‘the disc herniation position’. It’s hard to argue with the ‘pop’ of a sheep’s disc as it herniates after its 10,000th flexion cycle. But, with their computer models, Cavalier Karens have demonstrated that lifting and lifting posture are far more about trade-offs in different directions than ‘avoid The One Bad Thing and do The One Good Thing’. This seriously calls into question whether, out in the real world, avoiding bending and lifting is a reasonable strategy to avoid disc herniations.

Verdict: a mellee ending in a draw

Battle 2: Eager little adapters?

Sensing weakness, the Cavalier Karens move to seize the advantage. ‘This biomechanics talk is all moot anyway’, they say, ‘we aren’t dead pigs’ spines, we are living, moving, breathing human beings.’ (Some Cavalier Karens have a sentimental streak to them). ‘And people adapt to load. With bending and lifting, our discs get stronger - just like muscles and bones!’

To prove this point, Cavalier Karens usually point to a number of studies that show that runners, and perhaps some other athletes, have slightly healthier discs. And conversley, people who don’t exercise have unhealthy, more degenerated discs. “The disc lives by movement, and dies by lack of it”, to quote an old authority7. An extreme example: astronauts’ discs, which, without gravity, feel almost no force at all and therefore swell up unnaturally, which makes them particularly prone to herniation on returning to earth.

But the idea that discs are eager little adapters is not true.

For one thing, just because people who run more have healthier discs, doesn’t mean the running made their discs healthier. It’s more likely that runners are just generally-healthy and genetically-lucky people who also have nice looking discs. And anyway, a trial that tried to make peoples’ discs healthier by running didn’t find any benefit.

True, when you study discs cells in a lab, they do like load—but only moderate load at a moderate frequency. Anything more than that, they definitely do not like. In fact, antying more than moderate load is catabolic (i.e. they can’t recover from it and break down on a microscopic level). This is probably why the strongest evidence that exercise is good for discs is in those runners: running is exactly the kind of moderate, controllable exercise that discs would love and benefit from. And in fact, when you look closer at those studies in runners it’s the slow runners and even the walkers with nice looking discs, not the runners doing higher-impact stuff.

So why don’t discs adapt to exercise and movement very well? It’s mostly because there’s no blood vessels in the interior of a disc. The pressure is too high in there. And without blood vessels there’s no ‘supply line’ to get nutrients to the interor of a disc, and no ‘sewage pipe’ to take waste products away. Which means it can’t recover from exercise and adapt as well most other tissues.

It’s even worse once a disc is injured or degenerated (as many tissues are, it’s just part of life). Injured or already-degenerating discs basically can’t adapt to exercise any more. “Adult discs are incapable of repairing gross defects”, write one team of researchers. Another team says that “it is clear that an already damaged or degenerate IVD is unlikely to respond to loading in the same way that a healthy IVD does”.

The Cavalier Karen’s image of discs as eager little adapters who only get stronger with whatever you throw at them is… a mirage. Wishful thinking. The Cautious Kennys are sitting back in their chair looking smug (but with perfect posture).

But I’m being a bit hard on the Cavalier Karens. They are correct to point out that discs like (moderate) movement and exercise, which includes bending and lifting! So the Cautious Kenny idea that we should avoid bending and lifting to ‘protect’ a disc is indeed misguided. Again, there’s no get-out-of-injury-free card! If you avoid bending and lifting to try to protect your discs, you’re running the risk of overprotecting them, denying them the movement they need for their good health.

But, as we’ve seen, the Cautious Kennys are also correct to object that our discs are just not that good at adapting. They can herniate if they do too much too often, and they aren’t that good at recovering from injury8.

So what’s the verdict, are discs eager little adapters? Not at all, but nor are they fragile souls that need to be protected from the world. So this battle is a draw, too!

Battle 3. Out in the real world.

Let’s look at some real-world observational studies. Mostly these studies are of people at work.

Do people who lift and bend a lot have more spinal problems?

Yes. (See here, here, here, here, here, here...)

So, the Cautious Kennys claim a victory? If so, it feels like a hollow one. The association between lifting and bending and spinal problems is modest.

So modest, in fact, that many Cavalier Karens claim the research is a victory for them! ‘Let’s be conservative’, they say: ‘a modest association between lifting and bending and low back pain is tantamount to no association at all. It’s probably mostly issues with the studies: confounding, bias… If the Cautious Kennys were right we would have expected to see a much larger association!’

You might say that the real question isn’t association but causation. Does the research show that lifting and bending at work actually cause spinal problems? Well, here too there’s bitter disagreement on how to interpret the evidence.

For example,

A review by Bakker in 2009 concluded that association between “heavy physical work, and working with one’s trunk in a bent and/or twisted position and LBP was conflicting”.

But this review was criticised, mostly for categorising p values of more than 0.05 as evidence against an association, which they are not.A review by Wai et al. (2010) said “the evidence suggests that occupational bending or twisting [or lifting] in general is unlikely to be independently causative of low back pain”.

But this review was also criticised for 1) using a extremely high bar to prove causation, effectively setting the hypothesis up to fail given the state of the evidence reviewed, and 2) confusing the statement “there’s not enough evidence for us to say whether bending and lifting causes LBP” for “bending and lifting does not cause LBP”.A scoping review by de Bruin et al. (this year, 2024) concluded that “there was insufficient evidence to support a causal relationship between loading and the onset and persistence of [LBP]”.

But an editorial on the paper gently pointed out that de Bruin et al. had done the same thing as Wai et al. in 2010: setting an impossibly high bar, given the level of evidence available. “Assuming a multifactorial causation of LBP”, the editorial states, “applying the [criteria used by de Bruin et al] to any single factor will always lead to ‘insufficient evidence’”.

That’s all ‘low back pain’. Let’s bring this back to disc herniations and sciatica. Here, things get better for the Cautious Kennys. Because there is a stronger case that bending and lifting does cause disc herniations and sciatica out in the ‘real world’.

A study by Seidler et al. (2009) found "a positive dose-response relationship between cumulative occupational lumbar load and lumbar disc herniation as well as lumbar disc narrowing among men and women". For men, high exposure to occupational lifting had a 3.4 (2.2, 5,0) odds ratio for disc herniation. In other words, the men in this study who lifted a lot at work were roughly 3.4 times more likely to get a disc herniation. That’s about the same as the odds ratio between smoking and coronary heart disease, or obesity and diabetes, or air pollution and asthma exacerbations.

A meta analysis by Kuijer et al. (2018) found that there’s "moderate to high-quality evidence is available that [sciatica] can be classified as a work-related disease depending on the level of exposure to bending the trunk or lifting and carrying".

And a study by Bergman and colleagues confirms by direct comparison that disc herniations do seem to be more associated with lifting and bending than is back pain.

My take: lifting and bending a lot at work does cause low back pain (it would be strange if it didn’t), but a million other things cause/protect against low back pain so whether this is a meaningful cause on a population level is debateable. The case is stronger for lifting and bending causing disc herniations and sciatica, which makes sense because disc herniations and sciatica are much closer to a classic ‘overload injury’ type problem.

That said, remember this is all occupational. I don’t think there’s anything in these studies that says we should avoid day-to-day or recreational bending and lifting, whether that’s picking up socks, children, pickleballs or barbells.

Verdict: the Cautious Kennys take it, although not as emphatically as they’d like.

Battle 4: Cavalier Karens’ Trump Card

The Cautious Kennys fought valiantly, and had more firepower than many of you might have expected… I think they are right that bending and lifting causes disc herniations, but I’d qualify that to extremes of bending and lifting9.

In any case, the Cavalier Karens win a lot of ground in this battle by pointing out this simple fact:

For 99% of people out there, it doesn’t matter who wins a marginal victory on the topic of bending and lifting. That’s because there are other things—three of them!—that are probably bigger causes of disc herniation.

Those three things are:

One-time trauma.

A fall down the stairs, a sports injury, or a Sunday spent moving house. These discrete episodes of overload are kind of the ‘dark matter’ of research on this topic. How do you identify and measure them in a scientific way?10 As far as I can tell, most studies don’t.

But from what we know about the mechanics of disc herniations, and discs’ inability to recover from discrete injuries, one-time trauma is a very plausible Big Cause of many disc herniations. It’s not necessarily that a disc herniation would happen all at once just because, say, you fell while skiing. But given that discs are very poor at healing from injury, and staying healthy once injured, it’s likely that such incidents start some discs off down the path to a herniation, or expediate herniations that are already brewing for other reasons.General health.

If you smoke, drink, have diabetes or vascular diseases, then your discs have an even harder time staying healthy. Smoking, for example, reduces the metabolic activity of discs and weakens their structure. This might not be obvious but becomes more intuitive when you consider the effect of smoking on skin quality, and then extend that to other tissues in the body including the disc.

In other words, it’s not only the stress placed on the disc (by bending and lifting), but the health and integrity of the disc itself, partly determined by lifestyle, that cause it to fail and herniate11. Strangely, we readily accept this principle for things like major vascular events, osteoporotic fractures and tooth cavities, but there is a cultural blindspot around discs that only allow us to think about load.Genetics.

For decades, clinicians have noted that disc herniations seem to run in families. These observations were confirmed in the 90s by the famous Twin Spine Studies. You might have seen the MR images from these studies, of twins who entered very different professions - farmer and journalist, labourer and secretary - and yet ended up with very similar-looking spines. The Twin Spine Studies showed that twins with genes that increase their risk of disc problems—genes that make their discs’ collagen matrix weaker, for example, or make the enzymes inside their discs more active in breaking down the discs’ structure—are more likely to get disc problems no matter how much lifting and bending they do throughout their lives.

(Cavalier Karens sometimes grossly overstate the conclusions of the twin studies, though12. Heredity does play an important role in whether you get a disc herniation, but disc herniations are by no means ‘just genetic’.)

We can call these the Big Four causes of disc herniations: 1) bending and lifting, 2) one-time trauma, 3) general health and 4) genetics13. And bending and lifting is probably the little brother here, although it’s hard to weigh them against each other so I admit that’s a hunch.

Verdict: The Cavalier Karens win this battle. Bending and lifting are a small part of the big picture of disc herniations. And I think given how much territory the Cautious Kennys have lost, the Cavalier Karens are clearly winning this war.

Final message

For most people, this is my message on bending and lifting:

Bending and lifting is one cause of disc herniations.

But it’s a small piece of a big picture. In fact, bending and lifting is probably only a meaningful cause of disc herniations when it’s done excessively, such as with reasonably high-level lifting sports, or with years of occupational exposure.

That means if you avoid day-to-day bending and lifting, you’re probably not getting much benefit in terms of avoiding a disc herniation.

In fact, you might cause yourself problems by 1) relying too heavily on one way of moving, and 2) denying your discs the movement and force they need to be healthy. Do not let your spine wither away to reduce the theoretical risk of a disc herniation that might well happen - or not happen - anyway! “The disc lives by movement, and dies by lack of it”.

What about if you do bend and lift a lot, either at work or for a hobby? Well, other things being equal, you are probably increasing your chances of a herniation. If you are able to make changes to bend and lift less at work, you should do so.

But, even if you are doing a lot of it, bending and lifting is unlikely to be the decisive factor. Whether or not you get a disc herniation is probably more determined by your luck (in terms of whether or not you suffer physical trauma), your general health, and your luck again (in terms of what genes you inherited from your parents)14.

I suppose that makes me a Cavalier Karen.

I’m kind of lumping these together, although they’re different and often studied separately. Some people might say that lifting doesn’t cause disc herniations, but bending does, for example. Or vice versa. But I think for the majority of the public, they’re lumped together as a kind of ‘danger zone’. If you’re a layperson who’s wondering whether to worry about disc herniations, you probably just have a general idea that ‘lifting and bending’ might be bad. By contrast, you might have been told by your physio that actually, lifting and bending is great! And it’s those general conflicting messages that I want to address here. Please note I’ve also tended to use layman’s terms like ‘bent’ or ‘rounded’ back instead of ‘flexed’.

For clarity’s sake I’ve split up the two perspectives on this topic into these two camps. Apart from a bit of good-natured joshing, I’ve tried to be fair and reasonable to each and avoid pastiche or exaggeration for effect. Yes I do know that it’s not as simple as two camps who totally believe one thing yadda yadda. But as mentioned in footnote (1) I’m trying to address to broad, conflicting vibes perspectives that have purchase in different parts of the rehab, medical & exercise communities.

This might be via an annular fissure (the type of herniation you usually see on google images) or a mixed annular/endplate rupture. Either way is a herniation.

As well as bent-vs-extended spine lifting, the risk seems to balance out for stoop-vs-squat lifting. van Dieen et al: "The biomechanical literature does not provide support for advocating the squat technique as a means of preventing low back pain".

I mostly avoid talking about extreme extremes in this post, but it does look like loaded MAX flexion is more dangerous.

This is distinguished from a ‘neutral zone’ in between a bent and an extended spine, which is probably unattainable in real life and, even if it was, would be an undesirable way to lift all the time.

Gregory Grieve in his classic textbook

One common sense argument for this from Adams and Dolan is that the discs that herniate most frequently are the discs that bear the most load - the lower lumbar ones. There are other potential ways to explain this but the most parsimonious is just that load frequently exceeds discs’ capacity to adapt.

I feel like saying ‘extremes’ is a bit of a cop out on my part though. It sort of kicks the can down the road. (‘What’s extreme?’ ‘Well, too much…’ ‘How do you know it’s too much?’ ‘Erm, it causes a disc herniation’. ‘So… bending and lifting that causes a disc herniation causes a disc herniation?’)

I believe it’s similar in psychological research, where it’s just very hard to accound for one-off events (good or bad) in big observational studies.

My decision to separate this cause, general health, from the next cause, genetics, is a bit artificial, since one’s general health is partly a consequence of one’s genes. This includes lifestyle factors related to disc herniations.

If you actually read the Twin Spine studies, although they conclude that “61% of the variance in disc denegeration is explained by familial aggregation”, they were clear that familial influenece on disc health was lower - just 32% - in the lower lumbar discs, which are the discs that tend to herniate and cause sciatica. That’s a heritability index on a level with anxiety disorder, tobacco and alcohol misuse, and low back pain. Things that run in families, there’s no doubt, but are hardly ‘just genetic’. And nor are disc herniations. (Besides, apart from anything else, the Twin Spine Studies did not actually study disc herniations!)

The Twin Spine Studies can also be seen as part of a wave of ‘heritability-equals’ studies which appeared to be revolutionary and paradigm-shifting at the time, but which have failed to stand up to progressively more sophisticated attempts to quantify the role of genetics on particular traits. See for example the ‘missing heritability problem’ or the problem of variance and ubiquitous risk factors. Twin studies seem to overestimate heritability when environmental risk factors are common - just as are lifting and bending. For example, “twin studies show a very high heritability for obesity, even though time trend studies show that environmental factors are of overwhelming importance”. None of this is a criticism of the Twin Spine Studies, just of those who over-interpret them today.

How do the Big Four interact? All I could say would be “it’s complex”. I think for some people, one of the Big Four probably has an outsized effect and is kind of the ‘main character in the story’ (for example, I reckon a fall in my early 20s set me on the road to a disc herniation in my mid-20s). But for most people, it’ll be a pretty even combination of two, three or even all of the four.

I’ve deliberately limited the scope of this post to disc herniations, but I can’t help adding here that whether or not a disc herniation causes any symptoms is also dependent on things like general health, genetics and luck. Disc herniations that don’t hurt are very common! So there’s a kind of double layer of ‘other stuff’ between you bending and lifting a lot and you actually getting spinal pain.

I’ve been torn between these two sides, but I find myself drawn to the “cavalier Karens.” After one bout of back pain years ago, and now a couple months of pain from another back injury, I’ve gone through various approaches to dealing with the pain, with lots of frustration along the way. However, the game plan for recovery has become easier to manage, and I’m less hesitant to move in certain ways.

I’ve learned that back pain is complex, and there are no easy answers. I’ve worked manual labour jobs for years, and I’ve trained with weights for a long time, too, so I fit into a “high risk” category, perhaps, although there are some who might say that makes me more resilient. Either way, my recovery has been so personal, and at the end of the day I’ve had to find ways to stay active while winding down the pain, and not being hyper focused on restricting my movement too much.

Great article!

As people work longer and longer this will be important to understand especially for people that have to lift during work.