Welcome to the eighth edition of my sciatica newsletter!

This week’s podcast

In this week’s podcast, I talk to Michelle Angus. Michelle is a consultant physiotherapist working for the Complex Spinal Team in the Emergency Village of a tertiary spinal referral centre at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust. In this podcast, she tells me about:

Managing radicular pain in the ED

Spinal injections

Spinal surgery

Medications for radicular pain

And much more!

So long, gabapentinoids?

In the podcast, Michelle shares her clinical experience with prescribing gabapentinoids to people with acute radicular pain. Her impression is that while they do not work for everybody, some of her patients get meaningful relief. In last week's podcast, Kate told me that gabapentin helped her own radicular pain. When I asked on twitter, I heard (mostly) similar stories: "gabapentinoids are sometimes the only thing that allows my patients/allowed me to get any relief". At the time of writing, NICE guidelines for sciatica don’t make a specific recommendation on gabapentinoids; instead, they direct the reader to the general guidelines for prescribing for neuropathic pain, which approve them.

But, the draft version of the updated NICE guidelines for low back pain and sciatica (released some weeks after my conversation with Michelle) recommends against them. According to the draft update, there is no evidence to support their use for people with sciatica.

Where do we go from here?

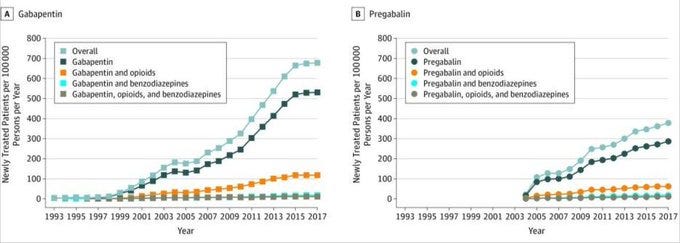

Gabapentin was developed in the early 1970s. It was approved in 1993 for seizures and marketed for pain soon after. Pregabalin arrived on the scene about ten years later. In the last two decades, their use has increased dramatically. Much of this has been “off label”, and the drugs have nontrivial side effects, so this increase is a cause for concern.

(Graph taken from Montastruc et al.)

Together we can call gabapentin and pregabalin gabapentinoids or anti-epileptics. Sometimes the term "anti-neuropathics" is used to bundle the gabapentinoids with tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline.

The gabapentinoids were designed to work on GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, which is where they get their name. It turns out they don't do this. Instead, it seems they primarily work on voltage gated calcium channels.

You will remember that when an action potential arrives at the axon terminal, voltage gated calcium channels open to let calcium into the neuron. The calcium causes this first neuron to release neurotransmitters into the synapse, which trigger another action potential in the second neuron. After a nerve injury, more voltage gated calcium channels are expressed on the end of the injured first neuron, so more neurotransmitter is released, so the second neuron becomes more excitable, which can increase pain.

These voltage gated calcium channels are made up of smaller sub-structures, one of which is the α2δ subunit. It's this subunit that the gabapentinoids act on. As far as I can tell, we don't know exactly how. One theory is that gabapentinoids stop the subunits from being transported to the axon terminal in the first place. With fewer α2δ subunits, one link is weakened in the chain of synaptic transmission. And so that second neuron is less excitable.

There is a good deal of evidence that gabapentinoids work fairly well for neuropathic pain. The problem is, we can’t say the same for sciatica. The draft update to the NICE guidelines refers to only three studies. One is small, lower quality and found gabapentinoids worked quite well. The other two are large, high-quality trials, and say gabapentinoids are no better than placebo.

On reading that these large, high quality studies found no benefit, my first question was: Did they select patients with *neuropathic* radicular pain? After all, radicular pain is a very mixed bag of nociceptive, inflammatory and 'nociplastic' mechanisms, to name just a few. But I would only expect gabapentin to be effective for the subgroup of people with neuropathic pain, meaning actually damaged, not just irritated, nerves. People with severe shooting pain, numbness, pins and needles, etc. If the trials jumbled up these people with all the other mechanisms of back and leg pain, then no wonder their results are negative.

Picture from Schmid, Fundaun and Tampin (2020)

At first glance, it seems like these studies did indeed jumble up the different pain mechanisms. In the trial by Mathieson et al., only a third of patients had likely neuropathic pain (as measured by questionnaire) and half had no loss of sensation (which indicates true nerve damage). And the other trial, by Baron et al., didn't give enough detail on the patients to say whether or not they had neuropathic pain, which implies they too were a mixed group.

But on closer inspection, both studies did account somewhat for mechanism-based prescribing. Mathieson et al. did a post-hoc analysis to see if patients with neuropathic pain benefited more. There was no evidence they did. And Baron et al. did try and target patients by giving them a mini pre-trial to see if they were "responders" to pregabalin before enrolling them in the main trial. In the main trial, this group of "responders" didn no better with pregabalin than placebo.

Besides, even if there is a subgroup of neuropathic-pain "responders" hidden in these two trials, for the trials to show a null result there would have to be an equal but opposite group of people who got worse taking the drugs!

Where does this leave us?

The way I see it, there are four positions:

1. "Gabapentinoids don't work for radicular pain". People are saying this more and more, and it is probably true in most cases. But, it has a ring of certainty that is not supported by the evidence. (This is a soap box of mine, but I think we need to stop being so cavalier in saying "X doesn't work for Y"; most clinical trials aren't able to tell us this).

2. "There is no research evidence to support the use of gabapentinoids for radicular pain, and good evidence to show they are not better than placebo when prescribed according to common practice. Although anecdotally they seem to work for some people, we have no way of knowing whom, so we shouldn't risk it". This seems reasonable to me, especially considering the harms of these drugs, which I have not covered in this newsletter. If we have no way of knowing whether and how often we are doing something right, how can we justify doing it? Better to just cut it out until we can figure out a better way (researchers are currently working on "sensory profiling" to target prescribing for anti-neuropathics).

3. "There is no research evidence to support gabapentinoids for radicular pain, and good evidence to show they are not better than placebo when prescribed to a heterogenous group. So, we should prescribe them sparingly and cautiously, and only in people who have severe neuropathic radicular pain". This seems reasonable to me too! We shouldn’t limit ourselves to research that is of limited pertinence to our clinical problem just because it's the only research that exists (as in the fable of the drunk who has lost his keys and looks under a lamp post because it's the only spot that's illuminated).

4. "Gabapentinoids work for radicular pain". It goes without saying, this statement unjustifiable.

How to choose between (2) and (3) is tough. Luckily, I don't prescribe, so I don't have to make these difficult decisions myself! But I do have to make decisions about whether to refer people to clinicians who do prescribe. At the moment (possible guideline change notwithstanding), I would refer for consideration of gabapentinoids rarely and only in the following conditions:

Severe, acute, disabling radicular pain

Neuropathic pain, preferably as measured by questionnaire (although these are not really well validated: a topic for another newsletter)

No option of epidural steroid injection any time soon

Either the clinician or the patient has a good relationship with the prescriber

The patient is in a service where they will get continuity of care and support with tapering if needed

As ever, I’d be really keen to hear your views, particularly disagreements and corrections.

Other bits and bobs

Who should I talk to for future episodes of the sciatica podcast? I have already had some good suggestions on twitter. As a reminder, I’d also like to talk to people who have experienced radicular pain or clinicians with interesting case studies.

The transcript of my podcast with David Butler is now available. Honestly, this was a huge ball-ache to write up, so I will see how useful it is to people before doing another one.

I think at the moment it’s a bit odd that the podcast and the newsletter arrive in the same email, so in the future I might put the podcast out midweek instead…

There was no newsletter last week as I was in Big Sur, celebrating my birthday and enjoying the return of the NBA :)

Big Sur view

With my niece, baby Ellie.