Thanks for reading the 46th edition of my newsletter. This newsletter tracks my research as I write a book about sciatica, and another one about cauda equina syndrome.

EDIT - an improved version of this post is here.

If I'm honest, when I first started practicing it took me a long time to get a good idea in my head of what CES actually is.

Although I was asking the CES 'red flag questions' many times a day, and I knew CES was something to do with disc herniations, I didn't really have a good grasp of the condition beyond that.

So in this email, I'm going to try to write a summary that I would have really wanted to read back then to help me understand CES.

(If you find some of the anatomy in this post a bit beyond you, this previous post might help.)

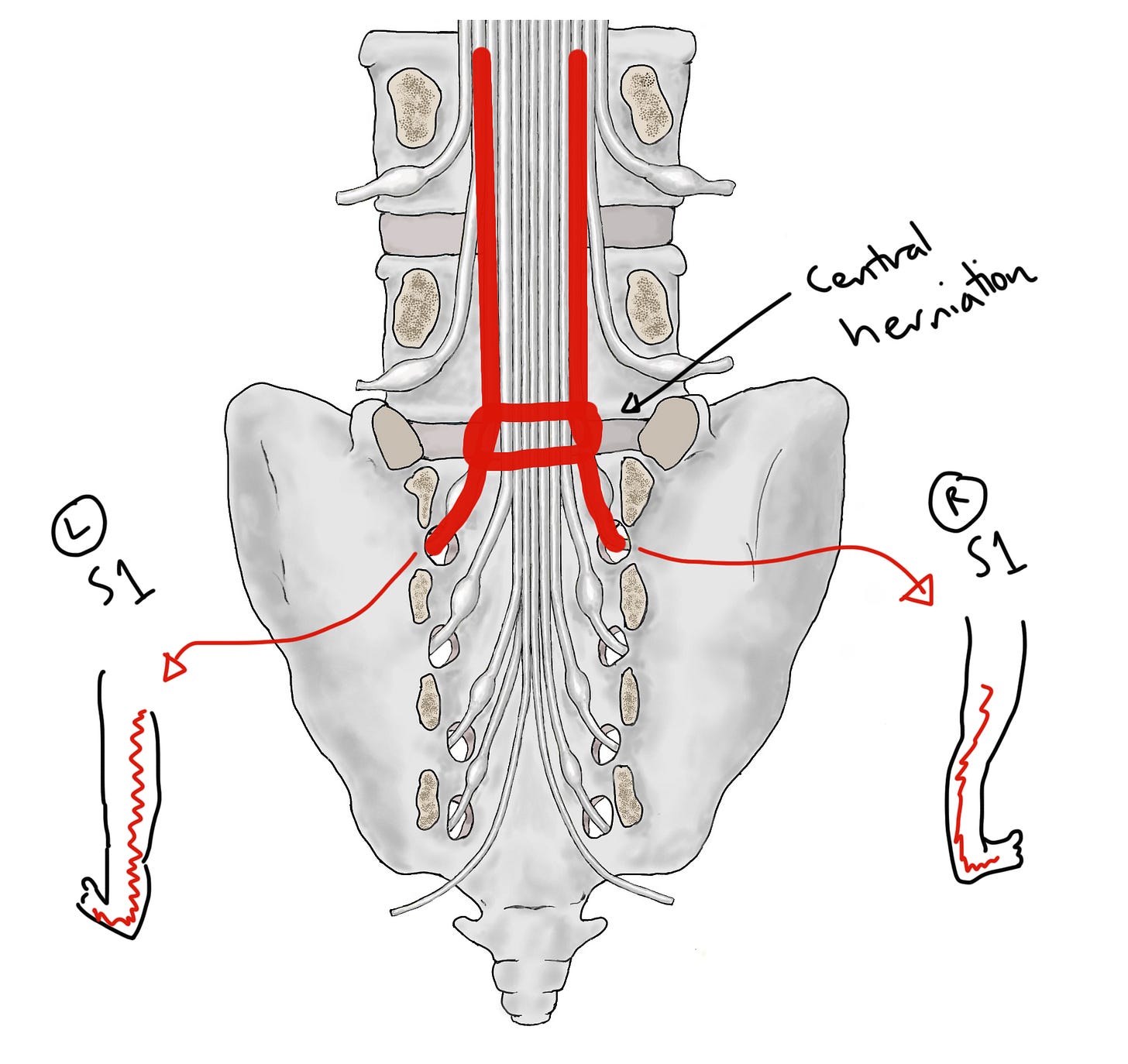

Here's a picture (from our upcoming book!) of the lumbar and sacral nerve roots. Remember the nerve roots basically link the central nervous system to the peripheral nervous system. This whole hanging bunch of nerves is the cauda equina.

Now let's split the nerves into two groups.

L4, L5 and S1 are all going to go into the lower limbs. When you do a neuro exam, testing strength, sensation and reflexes in the legs you're partly testing the function of these roots.

On the other hand, S2, S3, S4 and S5 are all going to go into the pelvis. When you ask your red flag questions about bladder and bowel function, sexual function and saddle sensation, you're asking about the function of these nerve roots. It's when these roots are injured that bladder, bowel, sexual and saddle function are all impaired, and we call this cauda equina syndrome.

How are these nerve roots injured? Mostly by things that press on the cauda equina. For example, vertebral collapse and vertebral slippage, stenotic overgrowth, tumours, aneurisms... But the most common cause is a disc herniation.1

However, it has to be a particular, rare kind of disc herniation.

The most common kind of disc herniation, which does not cause CES, is an off-centre herniation, at this point:

As you can see, this kind of herniation injures one single nerve root as it's veering off from the rest of the cauda equina. In this case, the right sided L5 nerve root. This doesn't cause CES, because S2-5 are unaffected. Instead, it causes sciatica (more properly called radicular pain or radiculopathy). Sciatica is really common, as we know.

At the risk of stating the obvious, this kind of common off-centre herniation can't injure S2-5 because... there's no discs in the sacrum, where those nerves veer off! Instead, the kind of disc herniation that injures S2-5, which does cause CES, is the more rare central herniation, at this point:

It might seem like a small difference in location, but you can see how it has a big effect because now S2, 3, 4 and 5 are in the firing line2. (To be clear, in the picture above I’ve marked the central herniation on the L5/S1 disc, but it could be any of the lumbar discs).

So this clears up a common point of confusion, which is that lumbar disc herniations cause sacral nerve root injuries, and therefore CES. It's because they injure sacral nerve roots as they're passing through, on their way to the exit points in the sacrum.

It might be worth looking at a picture of all that anatomy in 'real life'; thanks for Jose Paulo Andrade for the photo:

What else might I have wanted to know about 'what CES is', when I first graduated?

I think it would have been good to know a bit more about the leg pain. 'Bilateral sciatica' is a red flag for CES too. Why?

Well, if we go back to our picture of a central disc herniation, it’s quite easy to see how it can ‘catch’ both of the nerve roots that are going into the leg, too (in this case, the S1 roots), and cause bilateral sciatica.

The chain of thought behind bilateral sciatica being a red flag is: Bilateral sciatica! —> something might be pressing on both of this person's nerve roots! —> if so, that something is probably also pressing on their S2, 3, 4 and 5 roots! —> ?CES!!

(It's worth saying though, that actually about half of people with CES have unilateral sciatica... So bilateral sciatica is not necessary for CES3.)

Finally, I think the other thing I would have liked to have known back in the day is that CES is a condition that unfolds over time. We ask these red flag questions like CES is this static thing, but in fact the symptoms can unfold over hours, days or weeks, starting with very subtle signs and progressing, if it's not caught, to very serious ones.

Take, for example, bladder dysfunction. Most people know that urinary incontinence is a symptom of CES. But earlier symptoms might be less obvious changes to Frequency, Flow or Sensation (think FFS!)

For example, someone with CES might urinate more often than normal, because their bladder isn’t emptying properly (Frequency); or they might have to strain to start urinating, or find that when it comes out it’s just a sputter or a dribble (Flow); or they might not be able to feel it properly when they’re urinating, perhaps so that they only know they're going because they can see it or hear it hitting the water in the toilet bowl (Sensation).

These are all symptoms of an incomplete injury to the S2, 3 and 4 nerve roots... they've not stopped working, but they are working less well.

The incontinence is actually the end-stage of bladder dysfunction, when S2, 3 and 4 are barely working or not working at all. The bladder becomes paralysed and insensate and urine builds up inside. Once it builds up enough, there's no more room in the bladder so it leaks out: overflow incontinence.

So, there you have it. That’s what I would have needed to read to help me start to understand CES a bit better. I hope this post was useful to you if you’re at a similar stage now. There is, of course, much more to say, which I will try to cover in future newsletters.

Til next time,

Tom

P.S. I will let you know via this newsletter when the CES book is finished. Not long now… we’re currently making the final edits, and I’m trying to work out how to make it available and affordable in paperback.

Some people might object to the word ‘injury’, and also to some of the language about causation here. I get it, but I’m just trying to keep things simple here. Anyway, my readers are smart enough that I don’t need to caveat everything :)

It’s worth saying too that there are other structural reasons why CES is rare beyond just the fact that central herniations are less common. For example, the posterior longitudinal ligament is thick centrally, so it is an effective barrier between the herniation and the cauda equina. Also, the cauda equina has a lot of wiggle room which helps it to avoid compression, whereas the single, veering-off roots do not.

Bilateral sciatica is still much more concerning clinically than unilateral, however, because it’s so rare (i.e. even though half of people with CES have unilateral sciatica, far more people with bilateral sciatica than unilateral sciatica have CES).

Hi Tom I actually am one of those rare people that had to have emergency decompression surgery for ces. 12 weeks before this I had a stroke, pretty unlucky time just as the covid pandemic started, unfortunately when I went to a&e I was kept in 12 hours then discharged under sciatica, although I told them all the red flags and even asked if it could be ces but they didn’t listen, two days later after given an mri I was sent straight to surgery, I think there is so much more that needs to be taught to drs and nurses, students to be able to be more aware of ces red flags, as in my own personal experience very few drs, surgeons, nurses, still have very little knowledge of it and the aftermath destruction of lifetime disabling issues and pains were left with and still not believed or have a aftercare pathway. However I’m more than happy to help in any questions to better help drs nurses students gain more knowledge of ces.

Kind regards

Tantra

So clear and well written Tom. Graeme’s comments on common things is important too I feel . This is the way inservice education should be ! Do you refer to Jon stones scan negative research? The biomedical information is obviously important but so too is the amount of complex stress patterns coupled with depression etc . In a back clinic I worked in so many cases were a complex mix of things seldom needing neurosurgery intervention. Ian